Risk is a somewhat nebular concept, particularly in the context of major accidents. Although we are often driven to try to make it as precise as possible, there are inevitably several assumptions required to narrow down the inputs to a single number. A lot depends on the outcome of risk assessment; including how we focus resources to manage our more significant hazards. It is important to understand the results of an assessment and where they come from. How risk is presented is vital in how it is perceived and managed, but how can an intangible concept be made into something more material?

Tolerability as a Driver

One driver for presenting risk as a number is to compare it to tolerability criteria. When presenting the outcomes of risk assessment, a clear understanding of what is being assessed or calculated is required. Aggregated (or societal/group) risk determines the total risk based on the number of people affected and the frequency of the relevant event, whether that is one scenario or multiple hazards. Individual risk, however, considers the total risk to a single person from all hazards on an establishment.

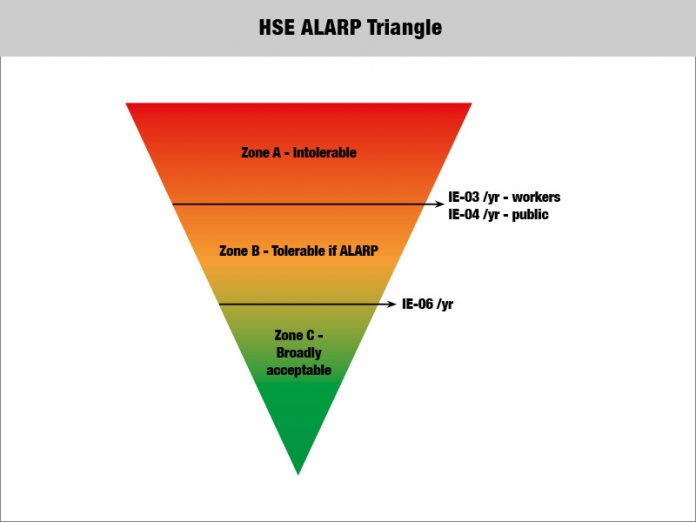

HSE guidance is helpful in providing tolerability criteria for individual risk, often referred to as the ALARP triangle, however there is less clarity for societal risk.

An F-N graph can be developed to illustrate criteria for societal risk using HSEs ‘Guidance on ALARP Decisions in COMAH’. The graph plots the cumulative frequency of events at an establishment per year (F) against the number of fatalities from all events assessed (N), allowing for the position of the assessed risk against the societal risk criteria to be presented.

It is important to consider that the risk criteria provided by the UK regulator are intended for the judgement of facility risk. Thought should therefore be given to whether or not adjustments are required for single and representative scenarios. By far the majority of risk assessments conducted are for single scenarios, and so direct comparison to the HSE tolerability criteria is not appropriate.

Communicating Risk

It doesn’t matter how detailed a risk assessment is if it cannot be communicated to decision makers and those exposed to the risk. Communicating a risk assessment should be more than a pass or fail against tolerability criteria.

In many contexts, the go-to for risk presentation is a matrix. Matrices are simple and visual, but it should be remembered that they are most appropriate for societal risk and can be misleading if tolerability is defined based on individual risk. A matrix certainly presents a risk picture, but it is only useful when the resolution and the tolerability criteria presented reflect its purpose.

Employers must share safety information with whomever it might affect. How this information is shared can be proportionate to individual roles and their responsibilities for risk management. Presenting risk against tolerability isn’t necessarily the best way to help decision makers allocate resources in the right places and is less helpful to other roles that may simply need to know the key hazards and what to do in an emergency. Consider the most appropriate way to ensure that the message is being received. Is a high-level awareness of hazards enough for the wider workforce, and how can the competence of leaders in understanding risk be assured? Note the focus on leadership by the COMAH Competent Authority this year means that, more than ever, these assurances must be in place and auditable.

The consequences of misunderstanding risk can be significant and so the method used to present risk must adequately reflect what has been assessed. It must be aligned to the correct tolerability criteria and reflect the scale of hazard being assessed.

Separating the concepts of risk tolerance and risk management can help make understanding of risks accessible and provide greater assurance that resources are focussed in the right places.

Carolyn Nicholls & Jennifer Hill