Researchers in Canada have unlocked some of the chemistry behind urban air pollution.

The team have determined for the first time that natural sunlight triggers the release of smog-forming nitrogen oxide compounds from the grime that coats buildings, statues and other outdoor surfaces in towns and cities. University of Toronto team member James Donaldson, Ph.D said: “The current understanding of urban air pollution does not include the recycling of nitrogen oxides and potentially other compounds from building surfaces. ”But based on our field studies in a real-world environment, this is happening. We don’t know yet to what extent this is occurring, but it may be quite a significant, and unaccounted for, contributor to air pollution in cities.”

Urban grime, according to Prof Donaldson, is a mixture of thousands of chemical compounds spewed into the air by automobiles, factories and a host of other sources. Among these compounds are nitrogen oxides. When in the air, these compounds may combine with other air pollutants — known as volatile organic compounds — to produce ozone, which is the main component of smog. Scientists had long suspected that nitrogen oxides become inactive when they are trapped in grime and settle on a surface. However, Prof Donaldson and his colleagues at the University of Toronto have collected data that challenges the theory. In previous work, they discovered that nitrate anions disappeared from grime at faster rates than could be explained by wash-off due to rainfall. In a subsequent laboratory comparison, they found that nitrate disappeared from grime 10,000 times faster than from a water-based solution when both were exposed to artificial sunlight.

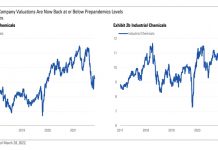

In another study, they exposed grime to either artificial sunlight or kept it in the dark. The grime exposed to a “solar simulator” shed more nitrates than the grime left in the dark, suggesting that light can chemically convert nitrogen compounds back into active forms that can return to the atmosphere. Prof Donaldson set out to test this concept in the real world. Working with colleagues in Germany, he set up a six-week field study in Leipzig and a similar year-long study in Toronto. The researchers placed grime collectors containing glass beads throughout both cities. The beads create more surface area for grime to gather on than a flat surface, such as a window. Some of the collection devices were left in the sun; others were put in the shade, but had adequate air flow so that grime could collect on their surfaces.

In Leipzig, the researchers found that grime in shaded areas contained ten per cent more nitrates than grime exposed to natural sunlight, which was consistent with the team’s laboratory findings. Prof Donaldson said: “If our suspicions are correct, it means that the current understanding of urban air pollution is missing a big chunk of information. In our work, we are showing that there is the potential for significant recycling of nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere from grime, which could give rise to greater ozone creation.” To test this idea, his team hopes to conduct field experiments in a place that is “really grubby” and someplace that is “really clean.” They also plan to examine the effects of humidity, grime levels and various amounts of illumination on the recycling of nitrates back into the atmosphere.

The work was supported by the American Chemical Society.